Jane describes the long and winding journey of being an older deaf learner driver.

How fast can you go?

For the past 30 years, my maximum self-propelled speed was 5.5 mph. And that was my ‘peak performance’ jogging rate.

Having learned driving basics with my Dad when I was 20, jobs in countries with difficult languages and winter-tyre requirements (Finland and Poland) then working in central London let me put off the idea of trying to take my driving test. Also, I seemed to be so busy all the time: any faint hope of reviving my driving skills disappeared over the horizon as I sank onto the sofa each evening, tired out after work, public transport travel and lipreading all day.

Fast forward, sitting at the edge of a local road for the first time in 30 years, ready to drive at the dizzying speed of 20 mph or so, I remember feeling utter terror. Cars thundered by. How on earth was I going to take control of this powerful vehicle and join them? My inner imposter voice screamed at me ‘What on earth do you think you are doing Cordell? You – a driver? Don’t make me laugh…’. For 5 bumpy years, with big Covid-related interruptions, I practised focusing entirely on the driving while telling the imposter voice to shut up and leave me alone.

My deafness added to the challenge. The first principle of driving is safety. It is what driving examiners look for and if you fail, it’s because you have done something which puts you or others at risk. As a deaf driver, you cannot lipread the instructor next to you. It would mean taking your eyes off the road and mirrors and that could potentially be disastrous. You, therefore, have to stop to discuss your driving and get feedback.

My learning journey was a long one with some interesting diversions.

Wrong turning?

The first teacher I tried had been recommended by BSL-user friends. She was lovely but I soon realised that trying to learn via BSL – my third language – was too risky because I could not understand instructions quickly enough. My vocal imposter voice took over and dented my confidence badly. At that point I decided me and driving were not made for each other.

It took another year for me to address the niggling, quieter voice inside saying ‘You can do it – you just have the find the right way for you.’

The right way involved:

- Choosing to drive automatic only. This was less to do with deafness and more my poor co-ordination (mild dyspraxia, I believe). If I wanted to be able to drive before my licence expired at 70 years old, I needed to give myself a helping hand!

- Focusing on tackling my confidence issues first with someone I trusted 100% and whose communication skills meant I could readily understand everything they said. This meant initially learning and practising, slowly and at length with a skilled driver who was also a professional communication support worker. It provided a coaching approach to driving which suited me as a professional coach myself.

This steady, unpressured approach started to gradually yield results, even if my first attempts to reverse park gave my inner imposter a field day! We sometimes took an unorthodox approach to the work, including planning longer drives on quiet roads with a ‘real’ destination, such as meeting friends. One of my proudest moments was having the confidence to be able to slap on the L plates and drive my husband a tiny distance to the local GP when he had an infection in his foot which meant he could not drive himself. Being able to park reasonably well at the clinic car park gave a moment of quiet euphoria.

When the wonderful ‘driving coach’ as I thought of them, said I was ready to work with a qualified instructor and prepare for my test, I felt terrified once again. How would I find the right person?

No through road?

Admittedly finding an instructor was a struggle. The few specialist driving schools for D/deaf and disabled people were booked up for months following the pandemic.

In the end I approached one of the best known and oldest and driving schools. The online booking system was restrictive. There was no opportunity to mention additional access requirements. This surprised me. There was also no mention of access on the website. The next point will be familiar to many deaf or disabled readers – I ended up spending quite a lot of extra time trying to communicate about my deafness. I tried Chat – but that was full, it said, so I left my enquiry in the queue. I emailed an address (once I could find it, buried deep in the small print of the website). No response. I tried again. No response. I had booked a lesson and paid in advance, so assumed all was well.

It wasn’t.

The evening before the lesson I had a standard text message from the instructor asking me to wear a mask in the lesson. It rang alarm bells as it suggested they had not received any of the communication from me. (You can’t lipread if you are both wearing masks). So I patiently explained again, by text message that I was deaf and that I had arranged communication support as this was the first lesson. The instructor seemed to panic at this. The said they would check with the central organisation in the morning. Next morning a message from the instructor they had not been able to get any useful advice. About one hour before the lesson, I received a standard ‘Your lesson is cancelled’ message. Confidence plummeted again and the Imposter was triumphant: ‘Ha – there you are. I told you so!’

As a deaf or disabled person you often encounter barriers like this. You have to decide whether to follow up or not. In this case I did. It took months. Communication was difficult. But eventually the company concerned apologised and promised to improve their website, but explained this would take time. I just checked now 8 months after this incident, and as far as I can see, no changes have yet been made. A pity.

Right turn

I reached a low ebb and asked for help. My husband did some research about local drivers. He had quite a long phone call with John Scott and after checking a few things, we agreed to give it a try. For John there was a lot that was new. He had never had a deaf pupil before. And he usually gave lessons in his dual-control car but because I needed automatic, we had to use our car. I think it is fair to say both John and I were a bit nervous and had a lot to learn! But quite quickly we figured out how to make it work. They key elements were

- openness

- flexibility

- staying calm and focused.

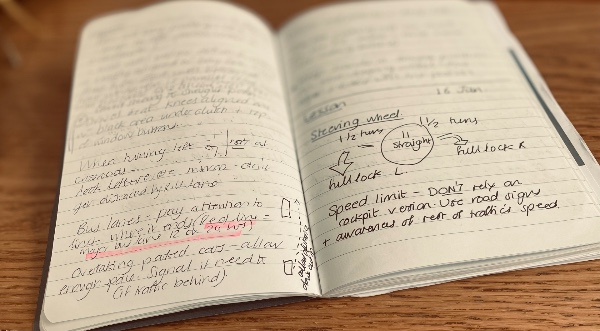

Communication while driving involved agreeing a simple set of gestures so that John could tell me the route to take. I was impressed by how quickly he picked these up, though later he admitted that the shift from being able to ‘talk constantly’ to his pupils, to being able to say nothing had taken some getting used to! We also made good use of technology including transcription apps on our phones. The advantage of these was that we I also had a record of the advice and feedback given. As an ‘R’ (reading and writing) type learner, I kept lots of notes to help me remember and practise mentally what I had learned.

Gradually, and with repeated practice, I started to feel cautiously confident behind the wheel. I even (whisper it) had occasional moments of enjoying being the driver.

Having taken no exams for over a decade, the prospect of both the theory and practical tests was quite alarming. I approached it by drawing on my experience – a tortoise, not a hare – preparing, practising, revising and doing it all hundreds more times. The electronic hazard test, similar to a video game in its set up and test of your reaction speed to visual hazards, was particularly tough at first and seemed much more geared to younger people, more used to online gaming. But I kept going.

Driving entered my sub-conscious. I had a dream that I was in the seat behind a driver and had to take over from the back seat. The driver transmogrified into a chirpy little Jack Russell dog, wearing a T-shirt with a red L plate emblazoned on the back. I woke up laughing!

Things continued to improve, but not always smoothly. Life ain’t like that. I had a ‘bad dress rehearsal’ moment during my second to last lesson before my practical test. Nerves – and that dratted imposter voice – took over and I did a truly terrible reverse park. I experienced an internal battle for the next 24 hours, fighting dark thoughts that it had all been a waste of time: how could a deaf, dyspraxic woman in her mid-fifties to try to manoeuvre a car correctly after more than 3 decades without practising? The other voice in my head said ‘It’s you, not a generic person and you can manoeuvre because you have worked darned hard and practised over and over again.’ I reminded myself of something the driving coach had pointed out: when I played the piano, I did not have to look at each key to check I was playing the right note. Through practice, I had reached the stage of ‘unconscious competence’ – being able to trust my fingers to hit the right keys. There were parallels with learning to drive and I tried to remember this.

Green light

John had been extremely helpful ahead of the test. He helped us secure a short meeting with the local test centre manager, who showed us the DVSA’s ‘Deaf pack’ of written instructions, worded exactly the same as the oral instructions. We also agreed to demonstrate to the examiner on the day, the set of gestures we had been using to show directions during lessons.

The ‘deaf’ side of things was covered; now all I needed to was to drive properly!

Although extremely nervous just before the test, I felt strangely calm as we started driving. I just tried to imagine I was having a lesson and do my best. I got one of the trickiest manoeuvres (parallel reverse parking on a slight hill and a busy road). There was a brief monumental battle with the Imposter voice, but I had so much experience of shutting it up by then, I was able to ignore it and focus on getting the car to do what I wanted.

The test seemed to pass so quickly. All those months of preparations suddenly culminated in the moment when the examiner flipped over the page of his Deaf pack and I saw the word ‘Passed’ and almost passed out with shock and relief. It was quite a proud moment to have to hand over the keys to my husband because I was now officially not covered by our learner insurance.

Straight ahead?

After gradually recovering from the genuine shock of finally achieving this long-held goal, I realised something. I could now drive alone. What a prospect! The first time I gingerly drove around the block locally, I kept expecting someone official to stop me.

Having planned to try to take my test for so long, I had not dared think about what came next. And what comes next is – yes, you got it – lots and lots more learning and practice.

It is a couple of weeks since my test. I have planned and driven a couple of routes with others in the car and barring one (ultimately useful) ‘near miss’ it has gone well. Now I need to ask John about some motorway lessons…